NATURAL HISTORY DEP'T.

A Quick Guide to Maryland's Would-Be State Fruit

BEING BOTH PAROCHIAL and hungry, Indignity was excited to learn that the Maryland Senate is considering a bill this session, proposed by a modestly politically connected schoolchild from Port Tobacco, that would name the persimmon the state fruit. This publication has a longstanding pro-persimmon editorial stance, even after the editor ate so many of the fruits a few winters ago as to end up nursing a long-lasting tummyache and searching "persimmon phytobezoar" on Google, and an enthusiasm for Maryland's existing official symbols (jousting! Rockfish! The Chesapeake Bay retriever!).

Nationwide, official state fruits seem to be odd or underwhelming in general, even by the erratic standards of state heraldry. Seven states have settled for apples, either of one locally relevant variety or another, or just apples generically; Arkansas, Ohio, and Tennessee have all pedantically selected the tomato. (Oklahoma, one of four states with strawberries as the official fruit, anti-pedantically named the watermelon as its state vegetable.)

Although the Maryland legislation names persimmons nonspecifically, it is reportedly meant to honor the state's wild-growing pre-Columbian persimmon, Diospyros virginiana. Although Indignity was aware of the local persimmons, the editor had no recollection of ever seeing one in the wild, let alone eating one. To learn more about the would-be honoree, Indignity spoke with Paula Becker, an outreach ecologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

Indignity: I'm a Marylander and a persimmon enthusiast, but I actually have very little or no direct experience with Maryland persimmons. So I'm sort of curious about the ecology and habits of this particular tree.

Paula Becker, Maryland Department of Natural Resources: Sure, it's a great tree.

Indignity: So I guess the first question is, where do you find them?

Becker: Well, you can find them almost throughout the entire state, except for the very high elevations up in Garrett County. So you will find them essentially from Frostburg east, all the way down to the coastal plain

Indignity: And they grow on the coastal plain as well as on the piedmont?

Becker: Yes.

Indignity: What's the range of habitats that they like?

Becker: They're very tolerant of a lot of different kinds of habitats. You may find them close to streamside—not necessarily in the heavy, flooded soils or heavily saturated soils adjacent to a stream, but close by. And you can find them also up on drier ridgetops amidst forests. They are not usually the canopy tree, but they're just under, in the sub-canopy. Their preference is for partial shade or full shade. So it's very common to find them in mixed hardwood forest.

Indignity: Which trees would be keeping them company in those forests, like what's the typical forest that they're in?

Becker: The only one you don't usually find them in are oak–hickory forests. You may see them in another kind of a mixed hardwood forest. It will very often have oaks and beaches and upland red maples, versus the red maples that like to hang out right next to the stream. Understory, you're going to find them very often with sassafras. In the shrub layer, it's very common to find them near spicebush or some of our highbush blueberries. So it's a tree that enjoys the company of other trees.

Indignity: Do persimmon trees cluster together with each other at all, or not?

Becker: No, you don't usually find them in big clusters. You find them scattered about. They're unlike other other trees that, if you were to cut them, they immediately sprout back and then you have a bunch of little trees in a copse. I have not seen them do that. I usually see the larger adult trees scattered about with a single stem, not usually a multiple-stem kind of a tree

Indignity: What is it about the oak–hickory forest that discourages them?

Becker: The oak–hickory forests that they're usually not found in tend to be the more upland oak–hickory forests, where there is a drier soil type or drier substrate. Which is not to say that they're not tolerant of any dry substrate, because I've seen them in fairly dry ridgetops, just not the really high-elevation ones.

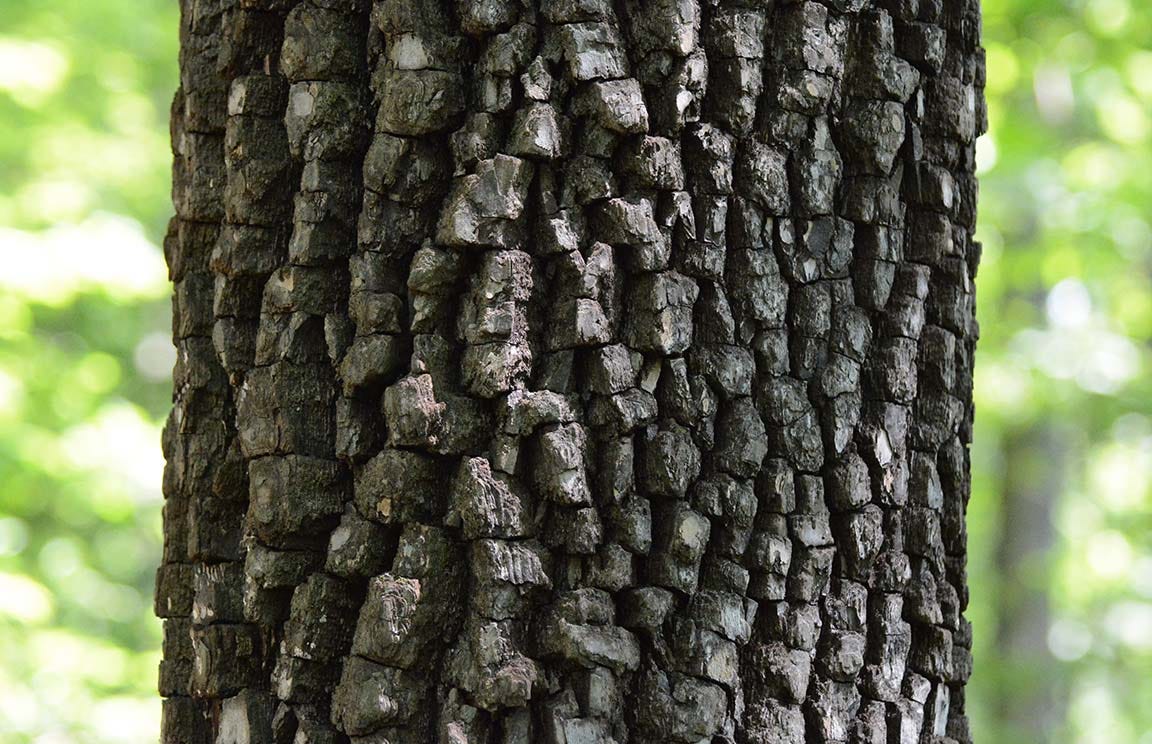

Indignity: What should people look for to identify the persimmon?

Becker: If you're looking at adult persimmon, a mature persimmon tree, the bark is really obvious. It's almost like a squared-off, wooden bubble wrap. It's very blocky. Usually the easiest place to find it is if you're walking through a nice mixed hardwood forest, and there is a space where there may be a slight opening in the canopy. They also enjoy being fully shaded, they can tolerate full shade. But I think the easiest place to find them is near a trail where there's a little bit of sunlight over the trail, but not full sun.

There's a really nice tree trail at Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Anne Arundel County. And there's persimmon right along the edge of the trail. Fortunately, there's also a sign identifying it as a persimmon. But when you look at it, and you see the bark, you realize it's not long, linear pieces of bark, like you might find in an older maple tree, where you have those long sheets or plates of bark. It's short, blocky bark that looks like really nothing else.

Indignity: How common are they? If you are going to just kind of dive into your nearest patch of woods and go looking, how likely would you be to spot one?

Becker: Well, the easiest time to spot them is really after the leaves have come off the tree when there is still fruit on the tree. Because then you look up and you see these sort of golden orange ping-pong-ball-sized fruits that have a slight waxy sheen. When you see that up against the sky, you realize there are not too many trees that have that shape on them at that time of year. The only other thing you might be able to confuse it with would be something like sweetgum, the sweetgum fruits, which are spiky balls. Or a sycamore fruit, which is also a round ball shape, but they come off the tree at a different time. So you just need to look around, look at the bark of that tree and those fruits and the time of year, and that's a pretty good indicator of persimmon.

Indignity: What months are they in fruit?

Becker: The best time of year to see the fruits is late summer to, say, September, October, November. The beginning of November is when they become easiest to see. And the fruit usually comes ripe around that time. Another way to identify them is to look down on the ground and look for the fruits that have fallen off the tree

Indignity: If they're if they're ping-pong-ball-sized, that's on the small side compared to the persimmons you might see in the grocery store, right? This is a small fruit.

Becker: Yes, the ones that you see in the grocery store are Asian species. They're sometimes called Japanese persimmon but they occur in other places in Asia and they were widely planted in like California, as a commercial fruit

Indignity: And these native persimmons are extremely astringent?

Becker: Oh, yes.

Indignity: These are the real ones that have to pulp up before you can eat them.

Becker: If somebody pulls one off of a tree and says, "Here, try this"—don't. I have found the only native persimmon that is safe to eat is one that comes very easily off the tree, meaning if a not-too-strong wind blew, it would come off on its own. Or when it's already on the ground. But before that, they're just—yeah, the pucker power is very strong in that one.

Indignity: Can you throw them in the freezer? Does that precipitate breaking down the astringent chemicals?

Becker: I have not tested it. I have heard of people doing that.

Indignity: Given the candidacy to be the state fruit, I was wondering what other contenders would there be? Assuming that people would want to focus on the natively occurring fruits, there's, like, pawpaw, what else?

Becker: Pawpaw is one. We have native blueberries and native cranberries. There are quite a lot of trees and shrubs that are edible. Whether or not you would want to is a different question. But quite a lot of our native trees and shrubs produce fruit that is edible. It all depends on what your tastes are. They all have wildlife value. They all are important for carbon sequestration and helping with climate change. And they all are really important with soil health. So from my perspective, they're all wonderful.

Indignity: But in terms of the ones that, for human consumption purposes, you would immortalize as state fruit, that sounds like the list of contenders isn't really all that long.

Becker: If we're comparing fruits, like the kinds of fruits you find in the grocery store, it's a shorter list. There are some that have a great deal of value, that people like, but they require a lot of work to harvest them in any large number. So persimmon, pawpaw, blueberries, cranberries, maybe some of our wild crab apples.

Indignity: Do the seeds get spread around by wildlife?

Becker: The beauty of the fruits is that they attract a lot of different species to eat the fruit, swallow the seed, transport the seed, and then excrete it somewhere else. And that's one of the ways that the seeds are distributed. Some of those fruits will also float. So if a tree is near a body of water, or if that fruit washes into a body of water, that body of water can transport the fruit. They're not really wind-distributed. It's mostly by animals and by water.

Indignity: Even ping-pong-ball size is still a pretty big fruit relative to birds and squirrels and things like that.

Becker: Yeah, a lot of the wildlife that eat them can be our larger wildlife. So things like foxes and bears. Certainly birds are a major transporter. Raccoons, possums, squirrels will eat them. Wild turkeys will eat them.

Indignity: Foxes will eat them? Foxes go for the fruit?

Becker: Foxes, like most dog species, are not 100 percent carnivorous. A large portion of their diet might be vegetable in nature. So they'll eat the sweet stuff. Coyotes as well. I mean, they certainly do enjoy the meat when they get it. But they will supplement with vegetation.

Indignity: Can they taste sweetness, foxes?

Becker: My understanding of canid taste is that it is less developed than humans. So it's less about the taste and more about the smell. They have significantly fewer taste buds than a human.

Indignity: This has been super helpful and informative. I'm glad that you're enthusiastic on these trees' behalf.

Becker: Well, I can't pick a favorite there. They're all important to me.

Indignity: You have to represent all fruits' equities equally, but—

Becker: I do value what persimmons bring to the party.

WEATHER REVIEWS

New York City, February 5, 2024

★★★ There was daylight shining through the slits of the shutters even before anyone got up from the breakfast table to open them. And there was light for running errands even after the children were back from school and settled into their homework—a real day's worth of light, from the rosy morning glow on the water towers to the golden late-day glow on the water towers. The cold was real but moderate; lotion was still necessary. A fan of pigeon feathers lay on the sidewalk, violently severed from the pigeon, still bound together by some pigeon-tissue near the ends of the quills. Sunset was a pink glow in the uptown end of the avenue and an orange glow in the downtown end, with a few wisps of pink cloud in the blue sky between.

EASY LISTENING DEP’T.

BLUESKY DEPARTMENT

EVERY DAY, READERS of Indignity have provided us with codes for the Bluesky social network, and on behalf of other readers who have benefitted from this generosity, we express our gratitude. Today we learned Bluesky is now open to all.

Open to all, eh? We’ll see how this works out! Meanwhile, be sure to follow Indignity on Bluesky: @indignity.bsky.social

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP’T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS for the assembly of sandwiches from The Old Vanity Fair Tea Room - Recipes Gathered from Far and Near, by Caro F. Chamberlain, published in 1927, now in the Public Domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

Miscellaneous Sandwiches

Chop fine, raisins, figs, walnuts. Add just enough mayonnaise to hold them together and a few drops of lemon juice. Put between thin slices of 100 per cent bread buttered lightly.

Take hot baking powder biscuits, split, butter lightly, and add a small round of frizzled ham and a slice of a small tomato.

Bar-le-duc mixed with Neufchatel cheese, put between split small tea biscuits.

Peanut butter and marmalade mixed and spread on thin slices of sandwich bread. Run under the broiler.

Pate de foie gras on thin slices of fresh rye bread, cut in small circles or triangles.

Grated pineapple, drained and mixed with Neufchatel cheese. Spread on thin slices of bread.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net.

MARKETING DEP'T.

Flaming Hydra is now!

EACH WEEKDAY, SUBSCRIBERS to Flaming Hydra now receive a newsletter featuring pieces written by two different members of the Flaming Hydra cooperative, an all-star collection of independent writers, on a rotating basis. Everyone chips in their bit, and the readers get a steady diet of items. And if the readers keep on subscribing, the writers keep on chipping in, and the whole thing moves toward being a self-sustaining publication.

The second printing of 19 FOLK TALES is now available for belated Holiday gift-giving and personal perusal! Huddle up against the cold with a cozy collection of stories, each of which is concise enough to read within the snowy part of a wintry-mix storm.

HMM WEEKLY MINI-ZINE, Subject: GAME SHOW, Joe MacLeod’s account of his Total Experience of a Journey Into Television, expanded from the original published account found here at Hmm Daily. The special MINI ZINE features other viewpoints related to an appearance on, at, and inside the teevee game show Who Wants to Be A Millionaire, available for purchase at SHOPULA.

INDIGNITY is a general-interest publication for a discerning and self-selected audience. We appreciate and depend on your support!