The Foreign Policy Community Needs an Intervention

AMONG OTHER THINGS, the end of the Afghanistan war has been a bad time for the feelings of the American foreign-policy discourse community. Their deepest worries are coming to the surface, although they tend to identify them as different worries. The accomplished international affairs journalist Susan Glasser, writing in the New Yorker late last week, offered a series of anxious questions:

Will the Taliban take Kabul by force? Will they march in before the upcoming twentieth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, which were planned and launched by Al Qaeda from Afghanistan, and which prompted the U.S. war there in the first place? Is there any realistic chance remaining of a negotiated settlement between the Afghan government and the Taliban to prevent such an outcome?

Even at that late date, the questions were getting some basics wrong. Would the Taliban take Kabul by force? No, not really, they just walked right in. Was there any realistic chance of a settlement between the Afghan government and the Taliban? By Sunday, it was clear that there wasn't enough of an "Afghan government" for the Taliban to have even negotiated with; if the government is who runs the country, the only government in Afghanistan was the Taliban one.

As for the middle question: yes, they did march in before September 11, 2021, but so what? Who cares? Joe Biden had offered September 11 as a withdrawal deadline in apparently the same spirit that led him to pencil in July 4 as the date things would be back to normal from the COVID pandemic, but anyone who even vaguely paid attention during the last two decades understands how pointless the 9/11 connection was. The Taliban are not Al Qaeda; the Taliban did not commit the attack. The New Yorker and Susan Glasser are well aware of these facts. It was emotional numerology posing as news analysis.

Compared to other experts on the wars, though, Glasser was coming only slightly unglued. Two decades of consensus—safe, respectable, mainstream consensus—about the inevitable and necessary and reasonable duties of a superpower had been chucked out. And not by the isolationist buffoon Donald Trump, though he'd laid the groundwork, but by Joe Biden!

Biden's handling of the evacuation of Kabul turned out to be thoughtless, incompetent, and callous. That is, it was as bad as the rest of the war in Afghanistan had been. To read the war experts in their moment of despair was to recognize that there was no other way it could possibly have come out—that no one, on the most basic level, had ever taken the war seriously.

This was how, just before reality set in, the self-styled “realist” magazine National Interest published an astonishing article by Michael O'Hanlon, the Brookings Institution's director of research on foreign policy. In it, O'Hanlon offered an alternative vision to the Biden withdrawal plan: more war. Specifically, he outlined a scheme to lock Afghanistan into indefinite civil war, or "a military stalemate."

To achieve this, O'Hanlon explained, instead of pulling its armed forces out of the country, the United States would deploy special forces and contractors to support the non-incompetent parts of the Afghan army and air force, would keep funding useful militias ("provided that the militias observe certain basic standards of human rights and restraint"), and would keep its own regional air power ready to rain down bombs if the Taliban threatened to make gains. But the Brookings expert wasn't simply dreaming of an escalated status quo. Instead, he envisioned what one might call a "final solution" to the Afghanistan problem:

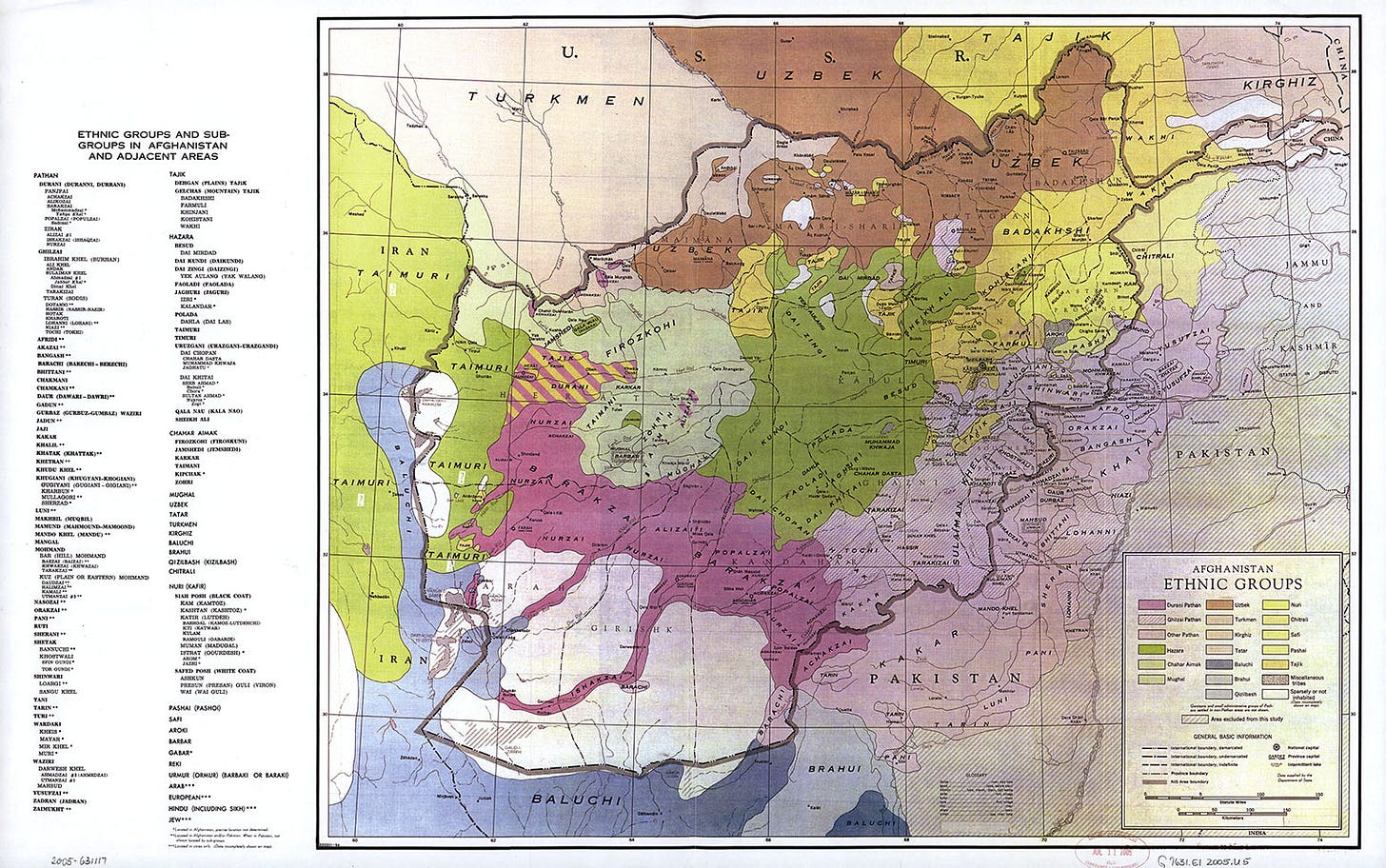

Develop a last-resort plan to relocate, humanely and safely, those Pashtun populations in the country’s north and west that provide cover, recruits, and support for the Taliban and that cannot otherwise be vetted or vouched for. The Pashtun, Afghanistan’s largest (but not majority) ethnic group, provides almost all Taliban supporters and sympathizers. Most Pashtun do not support the Taliban, but almost all Taliban are Pashtun. To create a dependable base of operations above the Hindu Kush mountains, this kind of step may ultimately need to be considered.

It's true, of course, that what O'Hanlon was proposing was an obvious, definitional war crime. The next day, after people pointed that out to him, he tacked on a frantic addendum:

I am not endorsing forced population movements as a preferred means of trying to protect northern Afghanistan and regret that I was not even more clear in describing it as a last resort.

It is to say the least fraught idea with a very bad history, and generally, when it happens in war it is NOT done safely.

But I fear that ethnic cleansing may begin to happen anyway, and in this context, would favor that it be prevented by a more managed process if and when there seems no alternative.

What was more revealing, even, than his daydreaming about an atrocity—even an atrocity "done safely" by a "more managed process"—was that the atrocity was also impossible. Targeting the people who tend to support and sympathize with an insurgent group is not a way to suppress the insurgency; it's the way to guarantee and deepen their support of the insurgency. This is a basic general principle.

And the specific case was yet more ridiculous. To control Afghanistan, one must simply move the Pashtun around? If the Pashtun could be shifted here and there around their native landscape to meet the managerial needs of outside administration, the Pashtun would already be peaceful citizens of the Afghan Soviet Socialist Republic, or loyal subjects of Queen Elizabeth II. Twenty years after the American invasion, the war expert did not know the literal first thing about military intervention in Afghanistan.

THOUGHT DEP’T.

Found Thoughts Division

Do you have a thought? Send it to indignity@indignity.net.