The Roberts Court doesn't need John Roberts.

“I WOULD GRANT preliminary relief to preserve the status quo ante," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote late Wednesday night, as the lone member of the Supreme Court's Republican majority to dissent from Tuesday night's decision to nullify Roe v. Wade in Texas.

Formally, the chief justice was referring to the status quo ante in Texas before its new law, SB 8, could take effect—the status quo in which it was still legal for a person to get a first-trimester abortion, without their doctors or associates being subject to punitive lawsuits filed by any member of the public who wanted to interfere. But a much larger, seemingly settled state of affairs was also slipping away.

The other members of the losing minority had strong words for the Texas law. Stephen Breyer called SB 8 "the invasion of a constitutional right." Sonia Sotomayor called it "flagrantly unconstitutional." Elena Kagan called it "patently unconstitutional." And that was all they had to say, three opinions, because that's what's left of the non-right-wing wing of the court: three votes.

Roberts would not go that far. He simply wrote that the parties seeking an injunction against law "have raised serious questions regarding the constitutionality of the Texas law at issue" and then noted that the consequences of letting the law take effect "counsel at least preliminary judicial consideration." But even that was a dissenting opinion—or worse, a meta-dissent: the chief justice, who sold himself to the Senate long ago as an umpire calling balls and strikes, now found himself trying to act out the role of officiating a nonexistent game. There was no contest between one side's argument and the other's; there was simply the majority delivering its chosen outcome.

The majority denied it was doing any such thing, or that it was doing anything at all, really. None of its members bothered to sign their name to their opinion, and their text even feigned agreement with their chief justice that the "applicants now before us have raised serious questions regarding the constitutionality of the Texas law." Yet as of Wednesday morning—hours before the Supreme Court got around to putting out any explanation at all—the law applied. Abortion after six weeks of pregnancy was banned in Texas.

If the majority sincerely believed the constitutional questions were serious, they would have followed Roberts and suspended the law from taking effect until the questions could be answered. Instead they took refuge behind the claim that the structure of the Texas law—delegating enforcement of the abortion ban to citizen volunteers filing lawsuits, rather than state officials—"presents complex and novel antecedent procedural questions" that would make an injunction impossible.

But the procedural questions were only "antecedent" to the constitutional ones because the majority decided they should be. "The Act is clearly unconstitutional under existing precedents," Sotomayor wrote, in a sentence that had been true 48 hours earlier.

Was it true anymore? "Constitutional" and "unconstitutional" are strange words, especially when Supreme Court justices use them. The justices write of constitutionality as if it were some outside condition that they are simply observing and reporting on, rather than the thing that they themselves are defining or creating as they write. The existing precedents ceased to exist as soon as the majority chose to declare that the procedural questions were more important; they dissolved the decades-old presumption of a legal right to abortion simply by offering a different presumption: that a first-trimester abortion ban can take effect while it is being challenged.

"Although the Court denies the applicants' request for emergency relief today," Roberts wrote, "the Court's order is emphatic in making clear that it cannot be understood as sustaining the constitutionality of the law at issue."

What the court's order genuinely makes clear is that under the majority's interpretation of the constitution, it is illegal to provide most abortions in Texas right now. People who could have gotten abortions last week cannot get abortions today, just as people who are being evicted from their homes because the majority struck down the CDC's eviction moratorium are going to lose their homes. In neither case did the Supreme Court go through briefings or arguments about the questions, but simply issued orders.

These orders—on the court's ever more busy "shadow docket"—don't need to involve deliberation or precedent. The majority readily reverses its stance on whether or not to allow nationwide injunctions depending on whether the injunction blocks or advances the Biden administration's goals. It rules first and justifies itself later, if at all. Two of its members owe their seats entirely to Mitch McConnell's abuse of the Senate's confirmation powers; a third openly ranted against his political enemies in his hearings. This is what the Supreme Court is, in 2021. This is, factually, how the constitution operates.

John Roberts, writing between the majority and the minority, regretted this state of affairs. He was critical of the fact that the Texas law will take effect without "at least preliminary judicial consideration," and that the Supreme Court was letting it happen "without ordinary merits briefing and without oral argument."

Maybe he even thought he meant it. Thanks to his refusal to throw out the Affordable Care Act and his court's unwillingness to help overturn Joe Biden's election, the chief justice has won himself respectable polling numbers with a substantial bloc of Democrats. Court-watchers credit him with a concern for the perceived legitimacy of the court, and a desire to restrain it (or to call for restraint, anyway) from the sort of raggedy and arbitrary performance it delivered on the Texas abortion law.

But this is the same John Roberts who discarded the fundamentals of the Voting Rights Act, who voted to abandon the limits on campaign finance, and who declared that the court had no power to correct abusive partisan gerrymanders. That, not Roe, was always the goal of his entire climb through right-wing legal institutions and the judiciary—to give legal authority to raw power politics, to fortify the Republican Party and its patrons against the political interests or desires of the majority of the population.

Now the faction Roberts worked so long to empower has control of the Supreme Court, and it doesn't care what the public thinks. The chief justice could write his lament about procedure if he wanted, but questions of legitimacy and dignity are out of his hands. The court he helped build was doing what it was built to do.

REMINDER DEP’T.

THE SOPHIST is here to tell you why you're right. Send your questions to indignity@indignity.net, and get the answers you want.

VISUAL CONSCIOUSNESS DEP’T.

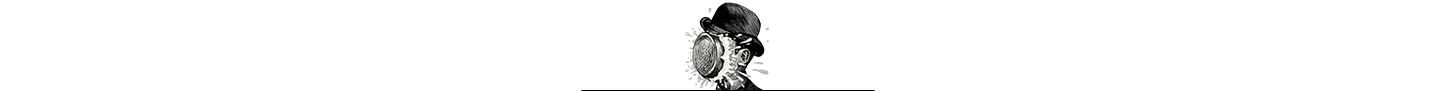

A Visit to the Price Club

More consciousness on Instagram.

THE HOLIDAYS DEP’T.

By Joe MacLeod

YES IT IS too early for this shit. There’s already a wall of candy corn at our local grocery store. So! Last year Halloween suburbia was all about the giant death-cult 12-ft. skeleton from Home Depot. This year Costco is attempting to horn in with this creepy-ass life-sized (death-sized?) “Sonny & Cher” lawn ornament, motion-activated to do some schtick and then launch into Cher and Mr. Bono’s greatest hit “I Got You Babe.”

The combination of empty cultural signifiers—skeletons, weddings, pop music—creates a hollow space which inevitably fills with the knowledge that Sonny Bono was killed skiing into a tree, so the married couple that originally sang "I Got You Babe" is 50 percent dead now, on average.

When reached for comment, Home Depot said:

and

and

This has been THE HOLIDAYS DEP’T. It is too damn early for this shit.

THOUGHT DEP’T.

Do you have a thought? Send it to indignity@indignity.net.